Last word is the lost word

Tom Verlane, 1947-2023

“You ever hear these guys?”

My boss Tony held a CD in an alpha security case. I put down the price gun and leaned over the rack of cutout cassettes I was pricing.

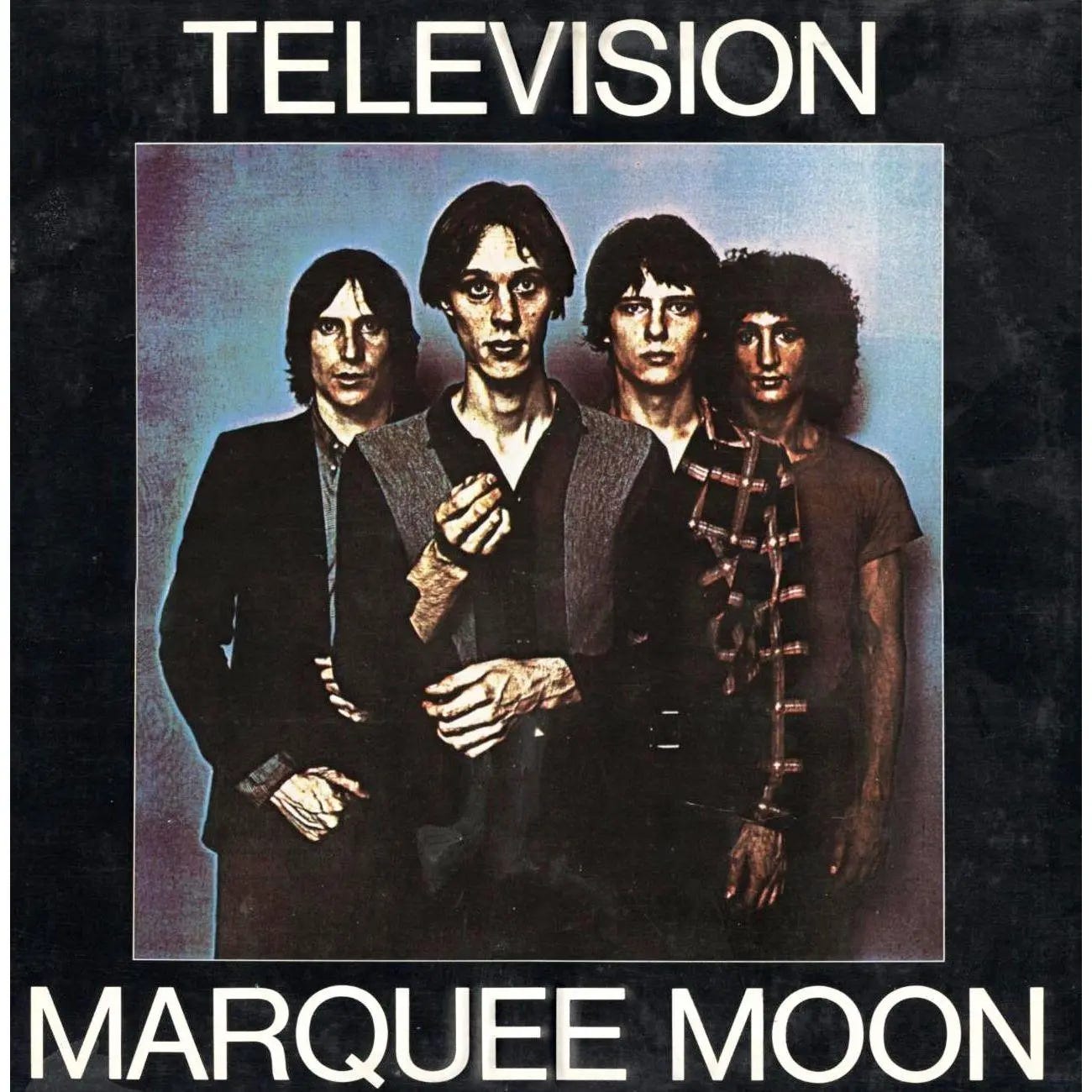

Framed in a black edging was a photo of four men standing in an aquamarine room, feathered hair growing into cowlicks and clad in shabby-chic flannels and suit jackets. One of them stood ahead of the other three, his direct gaze and the tilt of his forehead signaling that he knew you were looking at him and he was looking back at you. He held out his left hand in a gesture that seemed ecumenical, his right hand at his wrist like he was rolling up his sleeve. A sans serif font bordered the photo: TELEVISION above and MARQUEE MOON below.

I gasped; I may have bit my lip. I didn’t know men could look like that.

Tony jerked his head towards the counter. “I’ll leave it here for you,” he said. “I think you’ll like it.” He thought for a minute, rubbing the ends of his mustache with his forefinger and thumb. “It’s kinda like Fairport Convention,” he added, then shrugged. “You’ll see.”

When I interviewed for my job with Tony, I saw the postcard for the Richard Thompson album from a few years prior tacked over his desk and we bonded over our mutual love of British folk. “You’re probably the only 15-year-old in America who’s heard Liege & Lief,” he said with a chuckle before offering me a job on the spot. The Fairport albums at my uncle’s beachside cottage, with their earth-toned photos of the band at repose in green fields or seated around kitchen tables, seemed more bucolic than the icy angularity of the Marquee Moon cover art. My mother waited for me on a bench outside the mall, watching as Tony counted my stack of dollar bills and stapled a carbon-copy receipt to my shopping bag before telling me to “get lost.”

When I got home, I pulled my smooth Panasonic headphones over my ears and lay in the fetal position, sliding my discman under my pillow and keeping my eyes on my bedroom door in case Mom or anyone wanted to check on me. The jewel box for Marquee Moon sat on top of my clock radio if I needed to look up song titles.

Even with the volume at its lowest, the opening riff for “See No Evil” shot out of my headphones like an electrical current searching for an outlet. To say it was like nothing I’d ever heard before is cliché, but all the rock bands on the radio were playing distortion-heavy dirges grimy with reverb. Tony’s comparison to Fairport Convention seemed off as well; the guitar heroics were there, I suppose, but you could sing along with Fairport’s songs the first time you heard them.

This music was clean like a camera lens, each note played so it hung in the air for a split second before the next one sounded. Each instrumental part in the music sounded crisp and distinct—the melodic bass lines, the rolling drumbeat, the thrilling, direct guitar leads—but all of it added up to a swaggering whole that was greater than the sum of its parts.

I didn’t know then how many emails I would send with subject headers cribbed from these lyrics—indeed, I only had a dim awareness of what email even was—but lines and stanzas insinuated their way out of their songs, tossed off in a nasally voice that undercut anything that could seem florid and overwritten. Later I would learn that some found the singer’s voice hard to take, but his brittle, staccato delivery complemented his poetic lyrics. He wasn’t undercutting lines like “life in the hive puckered up my night/the kiss of death, the embrace of life” with a roll of the eyes to show you he was above it. The grain in his voice and his Noo Yawk accent existed side by side with his observations, the ungainliness of his voice complementing the elegance of his writing.

I got laid off from my job on the first Tuesday of 1994. My encyclopedic knowledge of unpopular music wasn’t enough to keep me on the payroll in the slowest month of the new year. The mall closed in 2016, and a Wegmans employee break room stands where I once locked CDs into security cases and priced discount tapes. I gave my copy of Marquee Moon to a friend’s classic rock-loving boyfriend a few years before a terrible fight cracked our friendship into a pair of silent halves.

Now Tom Verlaine is gone, too.

His death on Saturday morning came as a shock—he kept a low profile, but was sighted enough in the East Village that no one had any real reason to worry. Television had reunited for sporadic gigs over the past two decades, playing songs that should have been hits for an audience of stalwarts and of fans who hadn’t even been born when Marquee Moon hit the racks.

How do you mourn someone you never met, who nudged you further down a path that already appealed to you? I didn’t know then that “Marquee Moon” would be playing on my headphones as I traveled on a Greyhound to New York City for the first time, a city of concrete and chrome rising up around the bus as the solo on the title track gave way to an airy, arpeggiated melody. I didn’t know that reading about the making of the album would help me put the nicotine-stained cassettes on the floor of my father’s car into a wider context of New York City in the 1970s, that the call-and-response vocals of “Venus” would lead me back to the girl-group singles I dismissed as corny when I was in grade school, that Verlaine’s pen name and his lyrics would get me to try and read French poets of the Belle Epoque. I didn’t know where Verlaine was leading me, but—looking at the sleeve art for Marquee Moon as I listened to the fresh path his guitar solos beat—I knew I was ready for the trip.

Around the same time I worked the registers at my record store job, I was also the arts editor of my school paper, and I had placed a few stories about local music and theatre at area publications. My fantasy was to go to New York and work for Sassy or Spin. For reasons outside the scope of this newsletter, that never transpired. I settled into a mundane life in the suburbs and tried to shoehorn my artistic aspirations into the odd hours of my days…sometimes with disastrous results.

Over the past few years I found my way back to writing, both as a culture critic for a variety of web publications and as a songwriter and busker. As I got ready to record my debut album, my friend Bea suggested I try and get Tom Verlaine to play on one of the tracks. I shrugged it off at the time, because why would someone so groundbreaking want to work on my little album? Looking back now, I wish I had tried harder and at least reached out to him with an idea.

Verlaine’s passing leaves a huge hole in underground music. He changed the culture, and now he’s gone. Listening to Marquee Moon makes me aware of how much time has passed, but it also connects me with my youthful aspirations. May it do the same for you.